My Best Non-Fiction of Recent Years

Hi friends! Thank you all for your great engagement on my first-ever literary post on this blog. I’m back again for a follow-up to that article, this time tackling my favorite non-fiction reads instead of fiction.

Let’s clarify a couple things before we hop into this post, though.

First, these books did not necessarily come out during the last few years, but I did read them during the last few years. In fact, the two books by Krakauer came out in the 90s, and I first read Into the Wild in high school, but after finally making the leap to Into Thin Air in 2019 I have a whole new appreciation for his works.

Additionally, I am a huge history nerd, so while I read a ton of niche history books (most recent favorite: John Ashdown-Hill’s The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA) I’m not going to include those here. Don’t worry, I’ll have plenty of future posts about those, but I understand that’s not everyone’s cup of tea. I want to kick this blog off with compelling content that makes people want to come back, and I understand that a fairly dry book with size-10 font about one of England’s most controversial monarchs isn’t the best way to accomplish that.

…yet. I’ve got to hook you first and then you’ll care about Richard III as much as I do. We’ll get back to him eventually, though, never fear.

In the meantime, check out these reads which are completely Plantagenet-free.

Into The Wild & Into Thin Air – Jon Krakauer

I’m combining two of Krakauer’s books into one section here, because they’re irrevocably intertwined in my life.

Into The Wild, if you’ve not heard of it, follows the true story of Chris McCandless (alias Alexander Supertramp), a well-off young man who dumped his car, his money, and any way of contacting him immediately after he graduated college in favor of traipsing around the United States, hoping to find himself, meet people, and gain an increased appreciation for the life of a nomad. Infatuated with Thoreau’s works, Chris ended up in the Alaskan wilderness, living in an abandoned bus near the fringes of Denali National Park until the weather and an unfortunately misidentified bit of flora ended his life.

I first read it in senior year of high school in my AP Lit class. I think we all have a complicated relationship with books we were assigned in classes, but something about this one just got me. And I wasn’t the only one in my class with those feelings – after all, for a high school senior just about to break free from that oppressive suburban environment and explode onto the college scene (lol, we all wished) there was nothing more appealing than taking your destiny into your own hands, eschewing polite society, and living by your own rules.

I mean, Chris’s ultimate death was an issue, but that’s another thing high schoolers don’t think about. He had a good time until then!

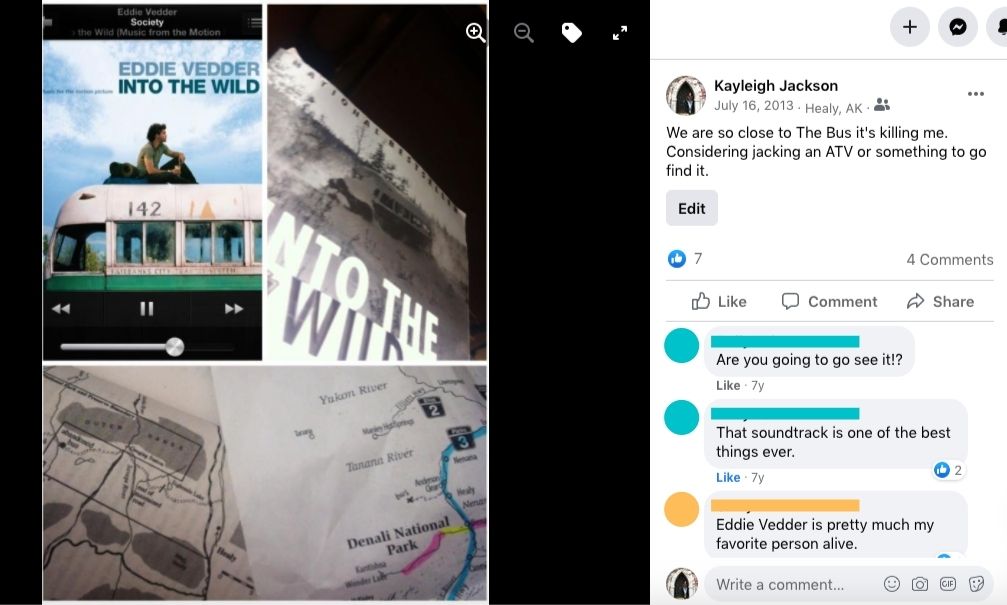

This book meant so much to me that, when my parents and I took a trip to Alaska in the summer after graduation, I had a full map and secret plot to sneak away from the tour group, rent a four-wheeler, and go out to the bus where Chris had lived, died, and been discovered. Naturally, at our closest point, the train did not stop, because idealistic 17-year-olds with no knowledge of the Alaskan wilderness do not control the well-oiled schedules and safety regulations of international tour companies.

But that’s not all … I may also have a tattoo of the bus number on my ankle.

You get it. I loved this book then and I still do now. I re-read it earlier in the pandemic, taking my new Jeep out to the highly civilized state park nearby on a rainy day and pretending I was alone and roughing it in the badlands, the world open and ahead of me.

So why did it take me seven years to read Krakauer’s other most iconic book, Into Thin Air? I don’t enjoy things casually (as you may be able to tell) and I was so into Mt. Everest in middle school I did multiple term projects on it. A book about the disaster of a climbing expedition Krakauer was on should have been required reading as soon as I snapped shut Into The Wild.

It’s petty, but I didn’t like the way Krakauer inserted himself into the narrative in Into The Wild. In retrospect, he was showing us the work he did as a journalist to reach out to Chris’s family, talking to people who knew and met him on his journey, sharing anecdotes to make us understand that our author too had once been young and stupid and could have turned out just like Chris if not for some luck.

But I wasn’t there to hear about Krakauer’s issues. I was there to hear about Chris. I might still skim those chapters even now.

That’s the difference with Into Thin Air. It is literally ALL ABOUT Krakauer’s experience, as a journalist who accompanied this troubled Everest expedition, stared death in the face, and whose reports changed hundreds of lives irrevocably. By the time I read it, I was a fairly recent college graduate with a journalism degree, and I was fascinated to read the accounts from base camp and the mountain – and even more fascinated to learn that other surviving members of the trip penned their own rebuttals, and that in the newer edition I had Krakauer rebutted them right back.

It was a journalistic pit fight set in one of the most extreme, dangerous places in the world, where I incidentally still want to go and climb up to Base Camp some day, because I don’t learn from other people’s mistakes. And oh, the drama. It was hard to remember that this was a non-fiction account, that these people really existed and many of them were long-dead, frozen or missing somewhere around Everest while families still mourned and sought answers.

I had to pull up the Wikipedia page’s account of the disaster to look at the trekkers’ images and remind myself that it wasn’t just an enthralling novel, to remind myself to read with the respect and seriousness the subject was due.

It’s funny how time and place can affect how you feel about books. I wouldn’t have appreciated the journalistic maneuverings of Into Thin Air if I’d read it any earlier, and I wouldn’t have appreciated the pure, escapist appeal of Into The Wild if I’d read it even just a semester later as a teenager.

Truthfully, when I re-read Into Thin Air, I think about the trips I’ve been on around the Australian Outback and throughout the rural Transylvanian back-country and what it would be like for an incident to befall a group as close as either of those were. It’s heartbreaking to attempt to paste that concept over a group of people I met, knew, loved, and then disconnected with over a short period – what the Everest trip should have been.

I’ll Be Gone In the Dark – Michelle McNamara

(TW: Rape, murder)

I’m not a big true-crime person, honestly. But everything about this book intrigued me. The author’s extreme dedication to unearthing the monster who was the Golden State Killer matched with her untimely death before the book’s publication was an intoxicating mix.

It was everything I hoped for and more. It was an extraordinary piece of long-form journalism, compounded from years of painstaking research and investigations into decades-old cold cases. It was exactly what I had dreamed about being able to produce one day as I sat through my journalism classes.

(I tried to avoid Wikipedia during this one, afraid I’d see any “spoilers” – if you can call them that for a real-world crime spree that made legitimate headlines a few years ago – so I lived in a small state of panic wondering if McNamara’s death was tied to the serial killer. For those of you interested in reading it, and also keeping away from Wikipedia for this reason: it was not, it was a tragic accident.)

Through her research, McNamara tied together three crime sprees around California that were previously thought to be unrelated, coined the nickname “Golden State Killer” to encompass the fiend behind them, and ultimately helped reveal and convict the man.

The details are, as you’d expect, gruesome, violent, and graphic, and not for the faint-hearted. The GSK was also a serial rapist, and some of the crime scene details are seriously affecting. You start to wonder how this mousy, twitchy, pudgy little man had the wherewithal and pure evilness to keep committing these awful acts and avoid capture for nearly 50 years.

One of the starkest details that stood out to me was not of a blood-soaked crime scene, or an victim’s account of barely escaping an early botched robbery alive. It was in the start of the book, when McNamara talks about “hunting the serial killer from [her] daughter’s playroom.” She makes lists of connections and suspects on colored construction paper with crayons so she doesn’t forget an idea, even during playtime with her young daughter.

It showed such an extreme dedication to both her craft and her family, being a loving mom and wife to a famous Hollywood star while also solving a major crime spree from the early 70s. Talk about multi-tasking.

Monsters in America – W. Scott Poole

It took a long time for me to understand, growing up, that there were so many ways people could be racist, homophobic, sexist, and otherwise horrible without it being overt. I figured, if people were just going to say and do damaging things, they’d just say and do them outright.

lol, wrong.

To that point, this was another one of the books where my own setting influenced how I read the book, and certainly how much I appreciated the content. To some degree, Monsters in America is about the actual monsters of film and legend we now accept as a core part of pop culture, but more so it’s a stark look at the origins and corruption of culturally significant lore to perpetuate stereotypes.

I started reading this book early last summer, shortly after George Floyd’s murder in Minnesota and amidst widespread protests across the U.S. (and much of the world) against police brutality. Even with my background in media and history, many of the stories in Monsters in America were new to me, with context I’d never have even expected to come up. But if you know what to look for, the dogwhistles and harmful stereotypes have been irrevocably injected not only into the horror genre, but the tropes and memes we’ve come to expect across our daily intake of media.

It made me keep my eye on the way the protests and government responses were addressed in media, traditional or otherwise. Yes, as a journalism grad, I know there are conventions one has to follow, and accepted ways to frame things – but now it almost doesn’t matter where we see a monster as long as someone agrees with us that it’s a monster. It can be in the newest film adaptation of Frankenstein or it can be in your nightly FOX News viewing.

I used to hate these kind of deep analyses, and some theories (not necessarily in Monsters in America, though) seem tenuous at best. And yet, once you look for the connections, they’re there. Someone is intentionally making these allegories and continuing to perpetuate them into a new generation.

Don’t believe me? I think this parallel says enough.

Valiant Ambition – Nathaniel Philbrick

Okay, I said I wasn’t going to get into weird niche history, and that was a lie. But it’s not as weird or niche as I could go, so you’re welcome.

Let me introduce this book with a story of my own:

Last fall, I was puttering through Vermont and New York on my way back from spending a few months in Maine. I’d planned my route back to stop at a couple cool Revolutionary War sites, staying overnight in Bennington, VT, and then spending some time the next day around Saratoga Springs, NY. (If you want, you can read my road trip thread here. The pertinent tweets to this book/story start here.)

I hate Benedict Arnold, right? I mean, everyone hates Benedict Arnold, but I really hate the man. I spent a lot of time laughing at the empty niche in the Saratoga Battle Monument where his statue would have gone if he wasn’t a traitor and a pompous windbag, and then went to go see the most hilarious, petty monument at Saratoga National Historic Park: THE BOOT MONUMENT.

Okay, so the park roads were closed for the season. The website didn’t tell me that. No big deal, I’ll just hike out to the monument. It’s only about a mile from the visitor’s center. I’m wearing heeled Oxford shoes, the battlefield is a muddy, hilly pit, and there’s a nor’easter heading toward New York that I’m trying to outrun, but I can do it.

Guess what else the website didn’t tell me, guys. Guess.

The monument was also closed for the season. It was sealed up in a neat little locked box where I could see nothing.

It’s been months and I’m still irate. Not to mention there was one other crazy gentleman hiking around the area so I couldn’t even start yelling at Arnold’s ghost, who was obviously haunting me and ruining my historical road trip.

So I hike a mile back in my heels, in the mud, in the winter storm, which is by now a downpour of freezing rain, cursing Arnold’s name like thousands of men on that battlefield did two and a half centuries ago.

So later that night, I reach my hotel in Cleveland and go out for a drink at a local sports bar. I’ve had a long, icy drive; Arnold is clearly having the time of his life (death?) haunting me; Clemson football is playing and I just want something enjoyable for two hours of the day and maybe a nice big ol’ stein of beer.

Somehow, I got to talking with a group of recently college grads near me. One was a freshly-minted history teacher. We both geeked out, naturally. At one point, I angrily declared, “People should be nicer to Richard III and meaner to Benedict Arnold!” (Told you we’d get back around to Richard III.)

Bless her soul, she said back to me, “Wow, you should be a history teacher too!” Based on… that statement? If anyone wants to take my course on “Controversial and Maligned Figures In British History I Have Many Feelings About,” let me know, I guess. It only covers those two people though.

So now to the book. Are you still with me?

I love Valiant Ambition because Nathaniel Philbrick is also mean to Benedict Arnold and Sir Henry Clinton, as one should be.

(To be fair, Clinton is mostly mean to himself. Philbrick just cites one of his correspondences where he calls himself a “sad bitch.”)

The thing that sucks me in the most to history books is when you can tell the author really knows and loves their subject, and isn’t trying to hide in the background as some faceless expert narrating impassively. Philbrick does that in all his books, and it is wonderful. No matter the topic, he is one of my flat-out favorite historians and authors. Of course you get the facts and the history and context, but the detail and personality within the writing makes you feel like you’re there.

There on the battlefield at Saratoga, surrounded by mud, and dying Revolutionary War soldiers, and me in my parka and heels shielding my phone and hair from the storm, all of us screaming at Arnold together.

You’re welcome! You’re only getting four sections instead of five, because really, there are five books listed and so much unnecessary personal history that you’d think you’re on a cooking blog instead of a reading blog, desperately trying to get to the recipe at the bottom.

What are your favorite non-fiction books? Are you more of a true-crime person, or a history nerd like me? (If the first, more power to you; if the latter, hit me up and let’s chat about our favorite eras).

Listicles Non-Fiction Best Books books Buying New Bookshelves Non-Fiction