Hot Tub Time Machine

One sub-genre of history I’ve accidentally found myself engaged in recently is that of the time traveler. These books ask, if you accidentally found yourself transported to this place and time in the past, how would you get by?

It’s a fun question to consider, especially as a lot of the history we study is big-picture stuff. As Ian Mortimer puts it in his introduction to The Time Traveler’s Guide to Elizabethan England, “You may well understand why the earl of Essex rebelled against Elizabeth in 1601 – but how did he clean his teeth? Did he wear underwear? What did he use for toilet paper?”

Crude as these particular questions may be, those are probably the first problems that would present themselves if you were magically dropped into another era. For me in particular, who has always been a big fan of Michael Crichton’s Timeline and whose first (very infant) novel plans to focus on time traveling as well, it’s certainly been a big question mark.

After all, if you have limited resources and limited time, you’re certainly not going to write about things you take for granted. Amplify that by about 1000 and it’s easy to understand why medieval – or even most working class, as society changed – citizens didn’t leave many details about day-to-day banalities. They don’t need to write down any specifics about their lives, about such activities as those Mortimer mentions above, because it just happened.

If anything was able to be recorded, it might be the weather surrounding a poor harvest, or the joy of a new baby in the family. More likely, most everyday people were illiterate and recorded nothing at all, further biasing the information of this ilk that survives to modern day. Upper-class folks who were literate and who were more likely to leave lasting information certainly had different garments, access to medicines and hygienic options, better (?) physicians, and so on.

Luckily, some authors have taken steps to put us into our ancestors’ shoes by sleuthing out these scant details and extrapolating them to everyday historic life. Unluckily, all the ones I’ve encountered so far are primarily focused on England. It’s understandable, given our Anglo-Saxon ethnocentrism, but keep that in mind.

Chronologically, we begin with Ian Mortimer’s The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England then move on to Elizabethan England, first mentioned above. Mortimer also has guides to Restoration Britain and Regency Britain, though I’ve not read these because I’ve seen “Bridgerton” and that’s all I need to know about the latter time period, thankyouverymuch.

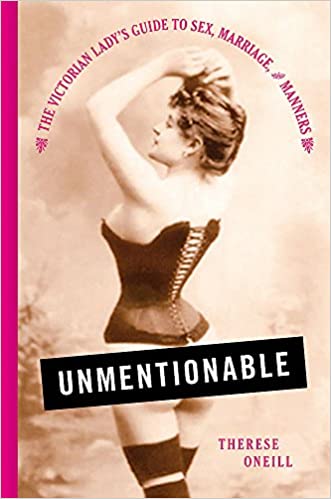

Another is Therese Oneill’s Unmentionable, which focuses on the feminine experience in Victorian England. The battle between propriety and actual, messy life as a human – who must eat, bathe, use the restroom, in some cases menstruate or give birth, and still maintain appearances – is astonishing.

That diagnosis of “hysteria”? Yeah, definitely understandable.

One of my least favorite eras of history to study is the Victorian age, industrial revolution and turn of the century. It was a grimy time full of technological developments and a lot of civil unrest. Overall, this time period of history feels like the color gray, but, like, a dirty brown-gray. Frankly, I don’t much enjoy any history after the American Civil War. Unmentionable cements that I wouldn’t have enjoyed it much had I lived then, either.

It’s a very informal book, but it truly is a guide to what you’d expect if, as a woman, you were suddenly dropped into the Victorian world, and also, if you had a fairy godmother hovering over your shoulder helping you through it. You’d probably land in a pile of horse poop, though, and then have to live with that because you’re wearing your one good dress and shoes, cleaning them is more work than it’s worth, and bathing might just make you dirtier than the poop did.

I love these books because we all like to think of ourselves as main characters. If we were able to time-travel, or live in a different era altogether, most of us like to imagine we’d be nobles or scholars whose names would go down in the history book and make an impact on society. We’d be someone worth studying centuries later.

Of course, that would be true of very few of us, as it is in the modern day. More than likely we’d be the serfs and the grunt soldiers, not the royals and generals. The closest you’d ever have a chance to get to Elizabeth I would be working in the stables or kitchen, if you were lucky and if your family had enjoyed that honor for the last few generations. No upward mobility here.

Now, as I mentioned previously, I recently started graduate school and I’m teaching a public speaking class. Every day, I take roll via an “attendance question” meant to get the students more comfortable with each other. I’m going to wrap up with a question here that I might steal for class – if I can get freshmen to think about history at 9am on a Monday in an unrelated class they already do not want to be in:

If you could truly time travel, what period would you go to? I don’t know if I could even pick one.

I do know which I wouldn’t go to, though, and that list starts and ends with the Victorian.

Listicles Non-Fiction blog posts books Buying New Bookshelves Listicles Non-Fiction

I would rather time travel to the future than the past. I want to know what happens in the future. How do we solve the long term problems the world is facing? New discoveries and inventions, and how and where do people live in the future. And most importantly, what has become of my family.

LikeLiked by 1 person